By Warren Perley

United Press International

April 27, 1987

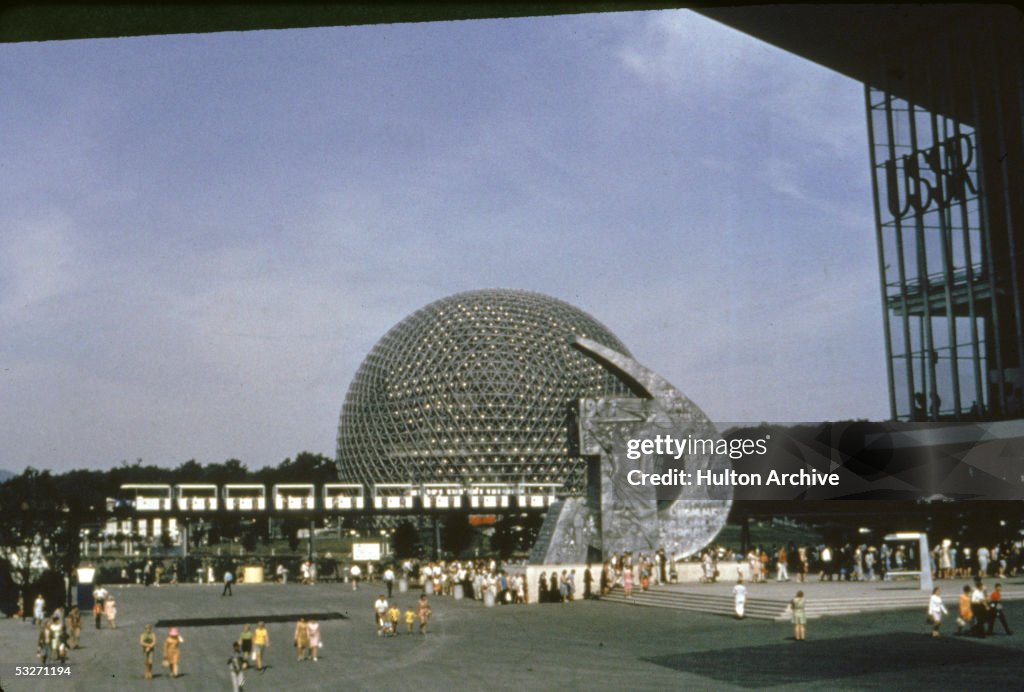

The Soviets’ sensitivity about their Canadian operation was never so clear as on a wintry day this year when they let their consulate burn rather than admit Montreal firefighters.

The result was a gutted three-story building and a very public suggestion that there was more going on inside than arranging tourist visas.

When the minor electrical fire ignited Jan. 14, consulate officials barred firemen for 15 minutes while they removed documents. When firemen were finally allowed onto the grounds, they attempted to break out some third-floor windows to make way for their hoses—only to find them bricked up from the inside.

When the firefighters were admitted to the structure, they still were refused access to certain rooms.

Afterward, Soviet Embassy official Igor Lobanov blunted questions about spying: “I won’t say anything about that.”

And the bricked up windows?

“Redecoration.”

And the documents that were more precious than the building?

Shrugged Mr. Lobanov, “You know, Western embassies in Moscow don’t keep copies of Playboy magazine in their files.”

What the West had was a tacit admission of what it has known for years—that the KGB was running a very active operation out of Montreal.

Canadian security sources said the third floor of the consulate contained a microwave communications centre that maintained contact with agents in Washington-New York-Boston areas. A rooftop satellite dish concealed in a wooden shed monitored phone calls to and from the U.S. and British consulates and U.S. defense contractors in Montreal.

The bricks in the third-floor windows were probably to block the laser microphones of Canadian agents trying to record Soviets’ conversations, a Canadian counterintelligence specialist said.

Jean-Louis Gagnon, a spokesman for the Canadian Security Intelligence Service—Canada’s equivalent of the FBI—acknowledges that Montreal is “an important area” for foreign espionage.

Montreal area companies do research and build weapons systems for NATO and the U.S. Defense Department.

Of the $145.9 billion in defense contracts signed by the Pentagon in fiscal 1986, $644.6 million went to Canadian companies.

“Those are classified materials that would logically be of interest to those people (the Russians),” Mr. Gagnon said. “Montreal is an important area for our counterintelligence operations.”

Western security agents say Canada, especially Montreal, is rife with KGB agents.

“The Soviets feel more secure in Canada than in the United States,” a contract operator for several Western intelligence services said. “This is where a lot of KGB agents come to get groomed before moving on to more sophisticated espionage and subversive operations in the United States.”

The operator, who said he had done numerous jobs worldwide for the CIA in the last 20 years, asked not to be identified.

He described Montreal as “a major centre for clandestine KGB activities involving espionage, subversion, terrorist training, and communications with enemy agents.”

The KGB’s primary target is always the United States, he said.

“They like Montreal because they can communicate easily with their U.S. based agents from here. It’s very easy for them to cross the border over I-87 using phony identities.”

KGB veteran Vitaly Yurchenko, who defected on Aug. 1, 1985, only to return to the Soviet Union three months later, was said to have headed KGB operations in North America between April and July 1985.

The CIA released a statement on Nov. 8, 1985, in which it said Mr. Yurchenko supervised the KGB staffs in Montreal and Ottawa and was responsible for recruiting double agents in U.S. intelligence services.

The CIA told a Senate intelligence committee that Mr. Yurchenko had been a genuine defector who had second thoughts, partly because his mistress—then wife of a Soviet diplomat in Canada—had refused to defect with him.

Another recent spy case involving Canada and the United States was that of Larry Wu-Tai Chin, a former CIA employee convicted Feb. 7, 1986, of spying for China.

The FBI said Chin, 63, made four trips to Toronto between 1976 and 1982 to deliver secret documents. He committed suicide before being sentenced.

The 1977 defection of KGB Col. Rudi Herrmann, who became an American double agent after the KGB tried to recruit his son, is another prominent case involving the United States and Canada.

Col. Herrmann, a Czech by birth, was trained in Moscow after World War II and sent into West Germany. He emigrated in the 1950s to Canada, where he worked until 1968 as a film technician for investigative journalists.

His job gave him a perfect cover for frequent trips to the United States, France, Germany, and all over Canada. He even acted as a soundman for a documentary on White House security.

Col. Herrmann was promoted to top KGB man in Canada before being transferred in 1968 to the United States, where he continued working for the KGB.

When he defected in 1977, he named Hugh Hambleton, an economics professor at Laval University in Quebec City, as a longtime KGB agent who had passed NATO secrets when he worked for the alliance in Paris in the mid-1950s.

As in all good spy stories, Col. Herrmann vanished in November 1979.

Intelligence sources say he, his wife and children were given new identities by the FBI and are now living in Arlington, VA.