By Ryan Augustine

By Ryan Augustine

August 7, 2025 Anno Domini

This is an article which I have hoped to write for some time. It is a follow up article which will draw on the foundation laid down in the previous article. This article will discuss the problems with the so-called “mixed economy” and the various forms of cloaked neo-socialist “3rd way” economic theories. Before diving in, it is important to understand these additional principles:

Inelastic vs elastic

In economics, an elastic price is when demand moves with the price. For instance, if a hardware store decides to increase prices 10% and they sell 15% less product, then hardware can be considered elastic. Conversely, inelasticity is when demand moves relatively little with price fluctuations—the classic example being healthcare, where if you break your arm, you will go to the hospital regardless of cost. The free-market tends towards elasticity, as competition allows the buyer to substitute goods and companies if a company increases prices. Socialism is inelastic because there is a quota system with a single supplier.

There is no such thing as a purely socialist or purely free-market system. In every socialist system, as discussed in the production problem, the pressures of demand and the incentive for corruption will always result in the formation of a black market and barter system. In a free market system, there will always be rules of commerce, that is, every marketplace will have rules which need to be followed. Even if there existed only two people: a buyer and a seller, there would still be the rule that payment is tendered for goods or services rendered. If either party does not believe that rule applies, then they are stealing. For instance, if a laborer sells his time to a farmer and the farmer decides to not pay him a wage at the end of the day, the “free-market” has become slavery. In this example, we may add the caveat that pure socialism may exist in this scenario; whereby, the farmer has set a quota and met his economic calculation of zero cost.

In this way, we should look at economies not as being pure socialism or pure free-market but as a continuum between the two where economies that have low taxation rates, God-given rights, freedom, competition, and low corruption may be considered to be free markets and those which have high taxation, little or no rights, are unfree, lack competition, and have high corruption may be considered socialist. This may go against conventional thinking that economic systems must be classified purely by political theory, but as shown in the previous article, the aforementioned qualities of these two economic systems are purely derived from their theories. Furthermore, for our socialist reader, the adage that true communism has never been tried is demonstrably false, because the pure theory can never be implemented due to the causative factors which emanate from the application of the theory. You may no more have an efficient communist economy than you can have a free market without rules; without rules, the free market no longer functions as free; with central planning, there is no price discovery and economic calculation is arbitrary. Following the philosophic principle that we may know a cause by its effects, we may view economic effects as being either socialistic or free-marketed. So even though a particular economy may claim to be 3rd way or neither capitalist nor socialist, if we see the effects of socialism in the system, we may know it to be socialistic, especially if the mechanism for the causation of the effects can be shown to be the same as in a socialist system. We shall use this lens to view the 3rd way economic theories later. This logically follows when we consider the free-market is the framework which gives man the most economic freedom and socialist the framework that gives man the least; therefore, every other economic system is bracketed on either side by the two.

This problem of the free-market needing rules and the inherent shortcomings of socialism has led socialist thinkers to develop what has been called the mixed-economy. The mixed economy is the economic system which seeks to combine the economic and societal controls of socialist (communist) theory while maintaining enough of the free-market so as not to engender the negative attributes of the socialist economy. They have become the norm in most western countries and some communist ones. Operating under the general plan of the perestroika deception, which was formulated in part because the Communist International realized that its communist countries simply couldn’t compete with the free-market economies of the West and so could not conquer them, communist countries have attempted to “liberalize” their economies to varying success. In Russia, which has been communist the longest, the corruption had so metastasized and the criminal ties to the Russian-Jewish Mafia so intense that this aspect of the perestroika deception failed. In communist China and Vietnam, it has succeeded.

In western countries, the mixed economy has largely come about from the efforts of Fabian socialists to establish the so-called “social safety net”, which is basically a collection of government programs and handouts with the stated goal to maintain a minimal quality of life level for those less fortunate. Like any good government program, or cancer, this “social safety net” has increased in size to socialize the therebefore free-market to such an extent that it may be now called a “mixed economy.” Thus, from the historicity of the mixed economy we can determine that a mixed economy is an economy which is controlled by socialists yet allows a certain amount of free-market activity to exist.

As the mixed economy lies somewhere in the continuum between the free-market and socialism, mixed economies are characterized by high taxation, some freedoms, some competition, lots of regulations over rights, lots of regulations in general, and a fair amount of corruption. In essence, rather than combining the “best of both worlds” of capitalism and communism as many claim, the mixed economy is a highly retarded version of what an economy would look like under free-market principles. This result is because the problems of socialism detailed in the previous article—the economic calculation problem, the production problem, and the immoral economy—do not vanish with the abandonment of pure economic socialism but exist on the continuum between socialism and the free market; likewise, the benefits of the free-market aforementioned also exist on the same continuum.

Part 1: The socialist problems and the mixed economy

Evaluating The Economic Calculation Problem and the mixed economy.

The ECP is not entirely eliminated in the free-market; after all, people are fallible and can only make the best decisions with the facts available to them. Yet, if we can visualize the ECP as cost clarity, then the free-market is akin to opening your eyes while swimming in clear water; socialism is when the water is silted out; and the mixed economy is muddy water. This is because in a mixed economy there are numerous hidden costs which are not captured by the market mechanism. These costs are, but not limited to: the burden of taxation, regulation, government programs, government employment, and increased inelasticity of goods and services.

Though it is touted that taxes are always passed onto the consumer, taxation increases the ECP because it is a hidden cost which increases opportunity cost and siphons money from those who are engaged in productive economic activities to those who are not. Because of the complex and progressive nature of taxes in mixed economies, these costs are, firstly, not always captured and, secondly, lead businesses and consumers to adopt varying strategies to mitigate them. These strategies include hiding income, reporting high losses, and various financial schemes. In essence, the taxpayer is incentivized to do his best to obscure his true costs from the socialist who is pulling the levers of the mixed market economy. Thus, the data which the social planner gathered by taxation to make economic calculations for his programs is, to varying degrees, inaccurate. A knock-on effect is fluctuation markets where companies have been incentivized to manipulate earnings and losses to avoid taxation. Very often stock prices fluctuate wildly when quarterly reports are submitted.

Regulations enhance the ECP for several reasons. They become barriers to entry by increasing the cost of business, thus limiting the number of firms who can compete in a market, and causing prices to be more inelastic. Regulations become a light backdoor version of quotas where if a business reaches a certain size, then certain positions must be filled by minorities and unproductive people. Regulations cause companies to engage in unproductive work which, thus, adds a hidden cost to the price, so that an increase or decrease in productivity is decoupled, to an extent, from price. So, for instance, if a midstream gas provider sees a surge in demand, their regulatory burden remains fixed and their prices may be elastic; however, if there is a decrease in demand, their regulatory burden is fixed and they may not be able to drop prices, thus, their price can be said to now be inelastic. This mechanism of the mixed economy makes the ECP for the socialist planner problematic because prices may not scale with production, which is always variable in a mixed economy. It may be argued that regulatory costs are subsumed into the overall cost of running a business, but the point remains that as costs unassociated with productivity are increased, the price relationship to production become proportionally unassociated with actual production of the good. Therefore, the true cost of production becomes less ascertainable, and the burden of setting accurate prices to the producer is likewise increased.

Government programs also increase the ECP for the social planner. They do so by adding hidden costs which cannot be accounted for by the price of the goods sold. For instance, it is a common practice in mixed economies to import labor from the third world, but while this labor drives down wages and in theory the cost of a good, the hidden costs of capital sent abroad and welfare programs to the family members cannot be accounted for by the company. So, for instance, if Saaraji Pooharti is imported to be a truck driver, the money he sends back to India is taken out of the economy, which is a cost not accounted for by his logistics company. Similarly, when he brings his wife and three children over and they go on various government programs, such as Medicare, welfare, head start, food stamps, public schooling, etc., these costs are not calculated by the logistics company in their price, yet they are cumulative to the economy as a whole. Thus, in a mixed economy it can be confidently said that the price mechanism does not accurately reflect the cost of goods and services when said goods and services are provided by those who partake in cost-adding government programs.

Government employment. The government in all mixed economies is the largest employer, by far. It makes sense, as all the programs and regulatory agencies must be staffed by government employees—most of which have become make-work programs for minorities. The government does not produce in a mixed economy, so all of its employees are collecting a paycheck for non-productive work. Following the laws of supply-and-demand, if supply remains fixed, as there is no production increase, and the available money in the economy increases through new wages, then the price will increase as new consumers have been introduced into the market. Thus, it can be said that the price of a good is not truly reflective of its production cost, as its price has increased due to external factors unrelated to the good entering the market. This brings us to one of the problematic effects of the mixed economy: that there is no way to cut government employment in a meaningful way without greatly hurting the economy. Because government is such a large employer, any drastic cut in employment will result in a drop in prices. Corporations are already burdened with hidden costs from regulations and the economy as a whole is burdened with taxation and government programs. Government employment acts as a backdoor for money to re-enter the economy which has been taken out through that mechanism by way of consumer spending. If government employees lose their jobs and go on government programs, this will decrease the amount of consumption in the economy and prices will be even more inelastic, as businesses which already have high overhead from programs and regulations will not be able to drop prices to compensate for lower demand. Because of this mechanism of hidden price increases, one can say that the tool of government expenditure reduction is broken in the hands of the social planner, and this is perhaps the strongest reason why mixed economies always tend towards socialism.

Some may ask, if there is no quota system, what is the point? The point is that there is no free lunch. All costs must be paid and when they are taken out of the price equation, they are passed onto the greater economy through taxation, inflation, and higher interest rates. This results in a lowering of the purchasing power of the consumer, which means that fewer goods and services are bought, thus, the economy as a whole suffers. It becomes problematic for the socialist planner to calculate why and make adjustments because the individual price points are not reflective of the overall health of the economy.

Evaluating The production problem in the mixed economy.

Following the continuum of free-market to socialist economies, the production problem of what to produce is hampered in a mixed economy. In a socialist economy, production is set by quotas, and in a free-market economy, it is set by the laws of supply and demand. In real-world mixed economies, this area is perhaps the aspect of those economies which is the most free-market like. However, the problem still exists in some ways. Because of the amount of regulation and government programs which function as a barrier to entry, mixed economies are characterized by large corporations and few actors controlling a disproportionate market share of the industries they are in. It is a fact that large organizations are less nimble and less adaptable than smaller ones. Therefore, they cannot make changes to production to meet market demands as quickly as smaller companies would. This means that in a mixed economy with large corporations, there is a certain amount of inherent waste and misallocation of resources that would not exist if smaller firms were able to compete. As a result, larger corporations are less sensitive to consumer demand. The internal structure of a large corporation makes decision-making timely and costly. Think of how hard it is to turn an ocean freighter compared to a kayak. A decision within a large corporation of what to produce is made at the C-suite level. For it to be made, it must pass through layers of data researchers, marketers, committees, finance teams, scalability reviews, reports must be written and reviewed, so on and so forth. In comparison, an entrepreneur may recognize a market need in the morning and have a prototype built in his garage that afternoon.

This fact of the internal structure of large corporations segways nicely into another aspect of the production problem which mixed economies encounter, which is what I call the Sovietization of the corporation. Because large corporations owe their competitive advantage to government regulations and programs, they are highly incentivized to be on the “right side” of them and inherently aligned with the socialist planners. This has led to the proliferation of the communist model of governance, namely the committee and the endless meetings. The image of the hard-driving, the-buck-stops-here capitalist boss is an anachronism. The fact is that few within large corporations like to take initiative and nobody likes to take responsibility. Corporate decision making is largely a function of top-down enforced consensus where the intermediate members of the corporation spend much of their time engaged in non-productive work. The effects are that, aside from an effeminate, soul-crushing culture, a large corporation becomes far less responsive bottom to top and top to bottom. Decisions and communications are filtered through layers and levels of committees, and the information takes a long time, if it makes it at all, to reach the desk of the decision maker. This, in turn, creates production problems, as the top management and the factory floor are decoupled by internal friction.

True story: there is a company, I won’t say their name, so let’s call them Pacific Electric and Gas. PE&G needs to inspect their powerlines from time to time to make sure they are in good condition. Instead of sending a couple of linemen to inspect their lines and write work orders to fix the problems, PE&G decides to hire an inspection company, because they are a risk adverse monopoly who can pass on the cost to the consumer. The inspection company hires lineman of their own for the job and within a few hours trains them to do the work, but before they can begin work, PE&G requires a third-party inspector to verify the inspection company is inspecting to PE&G standards. PE&G then hires a contractor to be the PE&G inspector of the inspectors. However, before work commences, PE&G requires that the inspection company inspection reports are quality-control checked before they are submitted to PE&G, so a third party quality-control engineering company is contracted to ride along with the inspection team. Once work begins, the inspection reports, after they have been QC’d, are submitted to PE&G, but PE&G does not review reports they have not quality-control checked, so those reports are rerouted to a different quality-control engineering company rather than being sent directly to PE&G. Finally, once the inspectors have been inspected, their surveys are quality-control checked, then QC’D again. Then they are all compiled onto a massive database where they sit for six months until the PE&G engineering team allegedly reviews them. The inspection company quickly realizes that there are so many layers of oversight that there is in fact no oversight. All that the inspection company has to do is not make a critical error with safety and reporting, so everyone in the field charges 12 hours a day and works 6-10 hours, depending on the day.

An Evaluation of the immorality problem in the mixed economy.

In the mixed economy, we see a retardation of the controls the free market provides against immoral behavior. As the mixed economy drifts towards socialism, there is a corresponding relationship to increased immorality in economic practices. Because, as previously shown, the mixed economy has high levels of taxation, regulations, and government, this necessitates money being added into the economy. Because the mechanism of adding money into the economy is through loans, this means that there must always be a net increase in money supply to pay the interest. An increase in money supply without an increase in production leads to higher prices, which is inflation. Because money on hand is always more valuable than money tomorrow in an inflationary environment, there is an imperative to have first access to money. This has led entities, such as large corporations and venture capital, to heavily prioritize financial schemes, which some term the “scam economy”. These schemes are where capital is raised through investments and loans, with the promise of future earnings being delivered upon a good or service provided. However, goods and services have costs, so the incentive for large entities is to underdeliver, or to not deliver at all, and use the corporate legal structure to allow the first users, i.e. ownership, to cash out. Such a mechanism mirrors the immorality problem of the socialist system; whereby, the manufacturer is incentivized to underproduce so that he can stockpile the raw materials. In the mixed economy, raw materials have been substituted for financial capital and the mechanism is largely the same.

Two examples come to mind. The first is Theranos, the famous company who promised novel blood tests. Theranos raised billions of dollars upon the promise that its new blood tests were a revolution in health care. However, these tests were fraudulent and the company was put out of business, costing investors their money.

The second example is that of venture capital creating Non-Fungible Tokens, or crypto-currencies. Venture capital has become a major player in the crypto market because it has realized that they can create a fraudulent product, take out loans and gather investments, pre-release the cryptocurrency to themselves, then when the public release happens, they can dump the crypto and cash out. Investors in the crypto are then holding a non-existent, worthless token and the venture capitalist pays back his loan and keeps the profit.

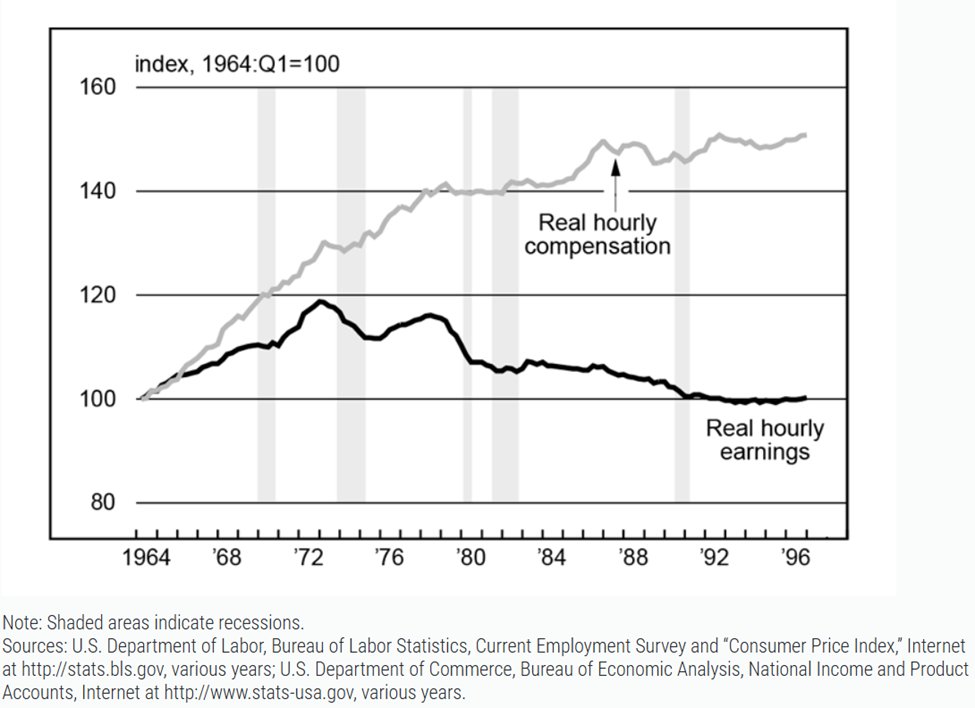

This leads to the second immoral problem, which is that mixed economies all have a growing wealth gap. Wealthy individuals and large businesses are the first recipients of new money because they have the credit and assets to provide collateral for new loans. Because of the first-taker effect and the incentives to put money into finance, these large businesses and wealthy individuals often use the money itself to make money and, therefore, the new money does not go to productive ends. Wealthy individuals, therefore, do not need to work in productive ventures, as they can live off the gains in investments at the same time as they grow their investment. This not only increases the inflation problem, by increasing the incentive to take out investment loans, but puts downward pressure on real wages, as an increase in wages is a cost which lowers the P/E ratio of companies and increases the incentive to investment. We may call this phenomenon a positive feedback loop, as the more money printed incentivizes more money printing and drives down the real wages of employees.

This graph shows the decoupling of real hourly earnings from actual wages, which began during the creation of the welfare state under the Great Society programs.

The negative aspect of this on the economy galvanized capitalist Henry Ford to institute higher wages and an 8 hour work day to solve this philosophical problem: If wages keep going down, who can afford to buy my product? Taking this truism and applying it to the economy as a whole, it becomes evident that the wealth gap created by loans, i.e. usury, as a function of the mixed economy leads the real theft of wealth from those who are productive while increasing the wealth of the very richest who are incentivized by the mixed economy to not work.

A large wealth gap creates an unstable society and an immoral society. This is because wage earners become highly dissatisfied with their decreasing class as their wealth is eroded away. Furthermore, belief in the economic system wanes, as those same wage earners can see the luxury which the unproductive members of society live in, whether it be from investments or from government programs. This creates an environment which is conducive to drug use and revolutionary activity. The dissatisfaction and vices then lead to an increase of police powers, surveillance, and the erosion of rights, which is the norm in a mixed economy.

It may be said that the free-economy does not have a direct mechanism to prevent fraud. While this is true, using first principles we can determine that the loose monetary environment necessary for mixed economies greatly exacerbates the scam-economy problem. Adding money into the economy is necessary in a mixed economy due to the sheer amount of money which is taken out for unproductive uses. Without the money supply being constantly increased, there would be no money in a few short years. Conversely, a free-economy does not rely on the creation of “easy” money, so there is more incentive to prudently make investment decisions and less pressure to invest. There is less pressure to invest because the free-market does not rely on an inflation mechanism. Inflation incentivizes loans because the value of present money is greater than the value of future money. In an inflationary environment, a loan payment decreases in relative value over time.

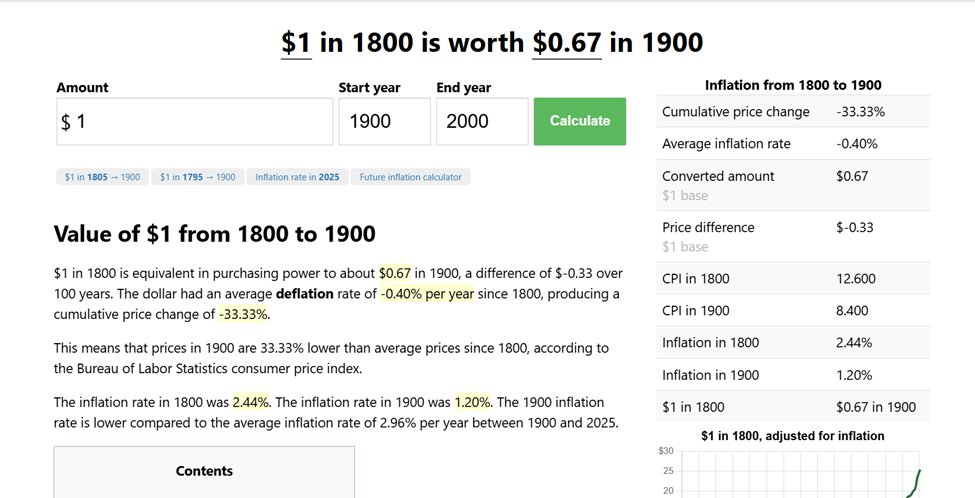

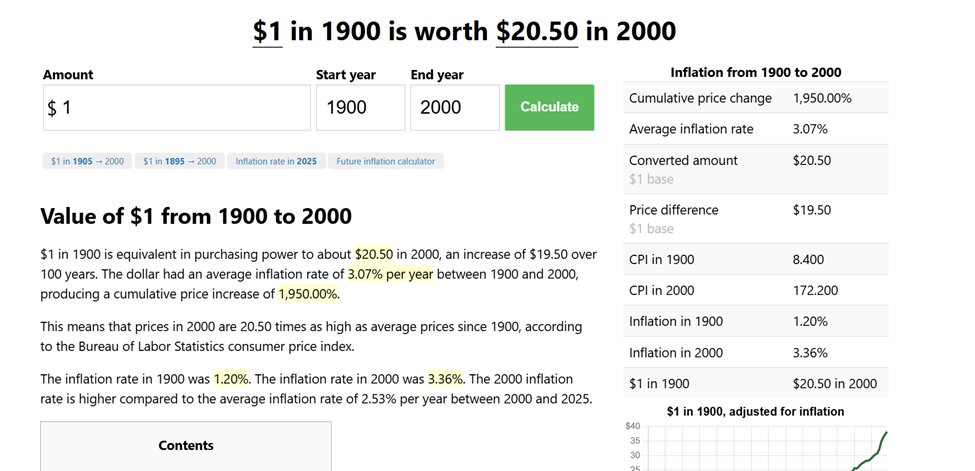

For example, in the United States from 1800-1900, which was perhaps the most free-market time and place in world history, the dollar gained 1/3 of its value. Meaning that prices were relatively stable and if you held onto your dollar for those 100 years it would have increased in value by 1/3. Compared to the following century, which saw the rise and establishment of the mixed economy in the same country, we see the dollar has lost 95% of its value due to inflation.

(5)

This figure actually underrepresents money creation, as gains in efficiency result in lower costs and, ergo, lower prices. For context, food was picked by hand in 1900.

Part 2: The eroding benefits of the free-market.

Since the morality problem has been discussed in part 1, this section will be brief. An effect of a mixed economy is a large wealth gap with dissatisfied workers; a function of the mixed economy is the dominance of large organizations who employ many unproductive people to comply with regulations, laws, and government programs. Combine these two factors and there is little motivation to follow the moral rules within an organization. Machiavellian principles are incentivized, as the ability to increase one’s earning power to stay ahead of the wealth erosion is decoupled from productivity. This is because in a mixed economy, a large corporation must balance (really prioritize) the needs of its unproductive members with its productive ones to stay on the right side of regulations, and the social planners. Furthermore, a large corporation with high barriers to entry and price inelasticity, both functions of mixed economies, is less production oriented.

The mixed economy and cooperation and social trust.

This section will be even briefer than the last. A socio-economic system which features a large wealth gap, dissatisfaction, scam-economies, and Machiavellian corporate culture is a system which will have low co-operation and trust between members. Coupled with an increase of social friction from third-world migration, the economic incentive increases to keep wages suppressed, and the trust within society, writ large, quickly evaporates.

The Mixed economy and the efficiency problem.

Any organization which is burdened by unproductive members, such as diversity hires, high regulatory requirements, etc., will necessarily be inefficient. We may think of a country as an organization and see that price becomes artificially inelastic, as only companies who can meet the high barriers of entry are allowed access to markets. Extrapolating to the price mechanism of resource allocation if prices become inelastic, which is that a producer may charge a higher price with no decrease in demand, then the efficiency of a market will decline, as the supply-and-demand mechanism which regulates resource allocation will cease to function as an efficient regulator.

Case study the American health care system.

No industry encapsulates the mixed market better than the American Health Care Industry (AMCI for short). A short examination of it reveals a Frankenstein showcase of all the problems of amalgamating socialist principles with the free-market.

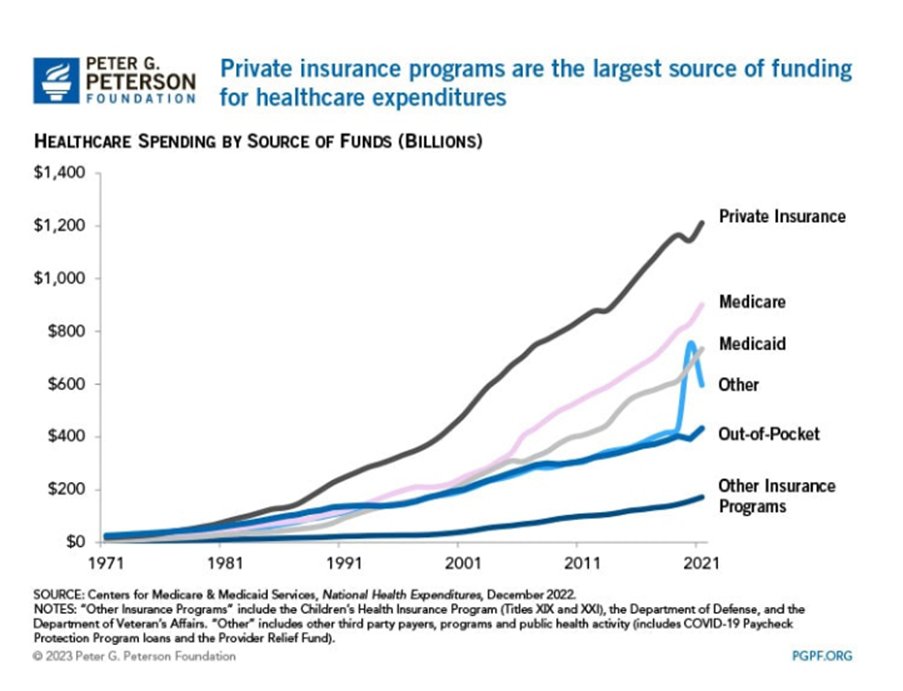

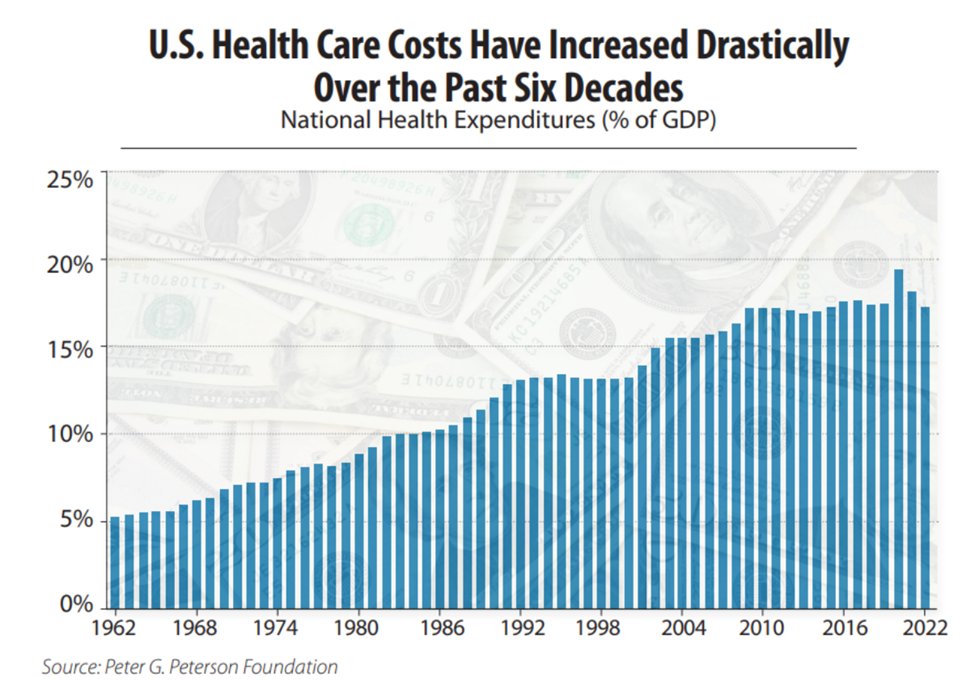

In a free market health care system, such as one that largely existed before the AMCI, health care was a transaction between the doctor and the patient where the patient paid for health care out pocket and prices were low and stabilized due to the market effects of the free-market. Because increasing regulation and programs such as Medicare created higher barriers of entry, large health-care organizations (HMO’s) formed and dominated the market. These HMO’s used their market share to artificially raise prices, due to the natural inelasticity of heath care pricing and due to the artificially created inelasticity from partial socialization. These rising costs created the health-care insurance industry, which charges a fixed premium in exchange for cost protection.

The insurance industry then compiles claims and negotiates with the HMO to reduce prices. This has created an immoral economy where both the insurance industry and the AMCI are incentivized to artificially raise prices. High prices force people into purchasing insurance for fear of being ruined and high prices are desirable to HMO’s for obvious reasons. It is immoral because the patient does not have a seat at the negotiating table and is forced to pay the full amount for services which the HMO does not pay to the insurance company as its normal operating procedure. Thus, it is evident that both the HMO and the insurance company operate as a protection racket where the HMO threatens the patient with financial ruin and the insurance company provides protection.

The relationship described above of a captive consumer base by the AMCI has other effects as well. Drug manufacturers are increasing their ownership stake in food suppliers, as the AMCI has realized that an unhealthy population will drive up health care costs. The AMCI incentivizes people to use Medicare and Medicaid, as the government does not negotiate prices and pays a premium. Thus, Medicare and Medicaid have become largely fraudulent, where patients are overprescribed, over treated, and incentivized to return to the HMO as many times as possible. This fraud extends to the whole of the AMCI to a somewhat lesser degree for the same reasons, namely to artificially drive up costs to the patient. There is a high level of Machiavellianism in this system, where patients must fight with insurance companies and HMO’s for their lives, often through costly legal battles, to pay for necessary treatment. This has led to the erosion of public trust and social cohesion within the industry, for obvious reasons. In short, the application of socialist principles to the free-market health-care industry has created what the socialist calls “predatory capitalism”.

Part 3: An Evaluation of “Third Way” Economic Systems

We may describe socialism as a system whereby the buyer and seller have no agency and we can describe the free-market as a system whereby the buyer and seller have perfect autonomy. Thus, as previously mentioned, all economic systems will reside somewhere in the continuum between socialism and the free market with mixed economies occupying spots somewhere in the middle. Mixed economies have been shown to be less than desirable economic systems because they are too socialist. Our evaluation of third-way economics is straightforward and simple: does the third way system increase the socialism of the mixed economy or decrease it?

Most all third-way systems increase the socialism of the mixed economy through the creation of more regulatory agencies, NGO involvement, metadata (AI) driven production quota schemes, decreased ownership, and other Klaus Schwabian Agenda-2030 styled programs. In essence, third-way economic systems are backdoor socialism.

Solidarism: A Case study.

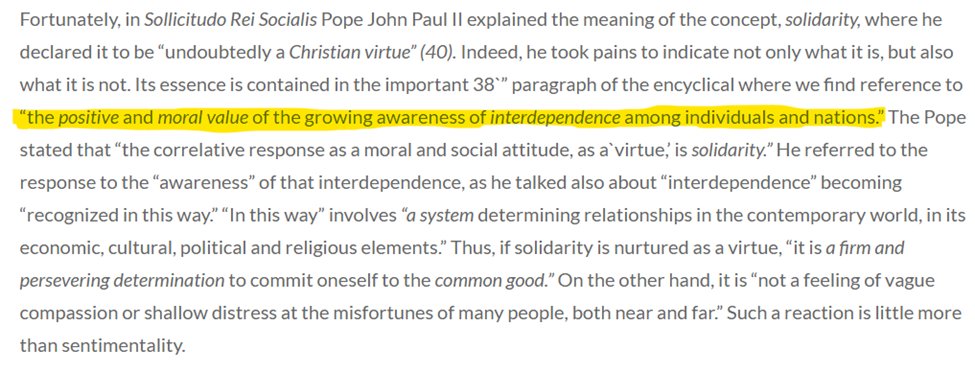

Fr. Heinrich Pesch was a Jesuit priest who developed the theory of solidarity during the turn of the 20th century. To be transparent, I have not read his massive work, Liberalismus, Socialismus und Christliche Gesellschaftsordnung. For the purpose of this article, we will discuss the Solidarity of Pesch through various Catholic articles, the communist solidarity theories, and see how the two have intermingled to produce what is commonly thought of as solidarity within Catholic circles.

First discussing Pesch. The Crisis Magazine article Rediscovering Heinrich Pesch and Solidarism lays out the principles of Pesch’s Solidarity taken word for word as follows (bold parts are the author’s emphasis):

- First, it rejects both individualism and collectivism and seeks to uphold the good of both the individual and society.

- Second, there is a solidarity among all men because of, simply, their common humanity. There is also a more particular solidarity among people in the same nation and within the same occupation or industry or area of the economy.

- Third, the worker cannot be reduced to a mere factor of production, nor can economics be made the be-all-and-end-all, so that everything is reduced to economic calculation.

- Fourth, the market and its advantages are accepted as givens by solidarism and economic freedom is a good thing.

- Fifth, in line with this, while there are certainly market inclinations and forces (e.g., supply and demand) they cannot be treated as rigid “laws” (a notion that came from the Enlightenment).

- Sixth, the sense of solidarity motivates the solidarist to promote occupational groups or other sorts of arrangements of those taking part in a particular industry—which must be voluntarily agreed to, and not imposed by the state—which would aim at a kind of enlightened self-regulation.

- Seventh, solidarism has no illusions about economic reorganization as some kind of panacea.

- Eighth, solidarism strongly defends private property, although private ownership—whether on the individual or large-scale corporate business level—can never be separated from the obligation of its social use (i.e., the concern about others and the community in the use of one’s property).

- The concern for socialization and the universal destination of created goods perhaps underlies the ninth and tenth points. While the state could step back with a solidaristic-type economic restructuring, its role cannot be minimal. Besides the proper kinds of interventions in the economy it must provide what in the Reagan period first came to be called a “safety net.”

- Eleventh, solidarism stresses the need for a just wage. This has direct implications for the state’s social welfare role: a just wage across the economy would mean that there would be less demand for public assistance programs. In line with its belief that nothing happens automatically in economic life, market forces alone cannot be the sole determiner of wage levels.

- Twelfth, solidarism is concerned about justice in pricing (which, interestingly, is an area that has not been developed much in the social encyclicals). A just price is one that both covers costs and yields the producer or trader a reasonable gain (a profit). While Pesch provides much more analysis about this, some of his key points are that the consumer has no right to the lowest possible price (the workers producing a good, after all, must receive a just wage), the price should reflect the true value of a good or service (while the solidarist believes that the satisfaction of wants, and not just needs, is legitimate, some wants—say, for moral reasons—clearly should not be pursued), and that no one should be allowed to make an exorbitant gain (including profit) at another’s expense.

- Thirteenth, any tax levied must be truly necessary, must take into account persons’ level of wealth, may be heavier on, say, investment income than income earned from work, and must be used to fund activities that will promote the common good and not merely the private good of some (e.g., interest groups).

- The fourteenth and final point is one that certainly collides with prevailing economic thinking: completely free trade must be rejected. This is because of commutative justice: certain countries are unable to derive the same advantage as others in a free trade regimen. Some would be hurt, as when cheap foreign products flood their markets and overwhelm their domestic producers. There is no problem with some measure of protectionism.

From the article, it would be unfair to conclude that there are not good ideas from Pesch which could act as a freedom catalyst in our mixed economic system if interpreted and applied with classical Catholic thinking. However, there is a lot of material, namely: the revolutionary attitude of solidarity, socialization of private property, progressive income taxation, social safety net, government regulation and programs, and wage and price controls, which already correspond to our mixed economy. In fact, it seems that there would be little difference between our mixed economy today and Heinrich Pesch’s solidarity, only with solidarity we would have a mixed economy cloaked in Catholic terminology. It is more difficult to imagine an attempt at solidarity, to ostensibly move us towards a freer economy, not being co-opted by socialists and perestroika change agents, since so much of the terminology and general ideas are inherent in both systems. In fact, this is exactly what has happened.

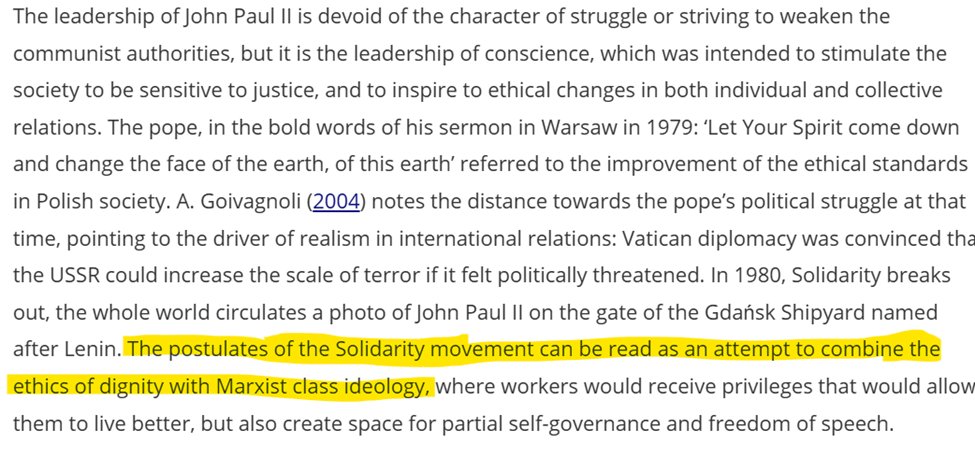

(2) Perestroika agent JP2

(3)

(3)

Solidarity as understood by socialists

(4)

As is evident from the quote above, solidarity is a revolutionary framework which the socialist uses to stir up the masses to subvert and ultimately overthrow a free economy. Solidarity may be called community organizing because its operational mode is to establish community-based networks to put economic and political pressure on the government and businesses to advance the socialist agenda. The communist solidarity in this respect operates as Heinrich Pesch envisioned the solidarity movement would, and this idea has been used operationally in many instances throughout the West. Such examples are the IBEW “Wobblies” communist labor union, various NGO’s, such as Soros Open Society, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and Saul Alinski’s community-organizing activities in Chicago. The irony is, of course, that Solidarity in practice is used by repressive regimes and wealthy communists to inorganically transform the economy along socialist, atheistic lines.

It should be clear why socialist change-agents such as E. Michael Jones appeal to Pesch. It is to use his ideas to advance world socialism. It is doubtful that Pesch would approve of socialism as we understand it today; however, his work can so easily be applied to making the socialist case for economic control under the cloak of “Catholic thinking”. Therefore, solidarity as a whole should be rejected as a viable third-way economic system.

Final notes:

It should be emphasized that a pure free-market is unobtainable. Every voluntary transaction has underlying rules which must be followed in order for the transaction to freely take place. The rules must have an enforcement mechanism or else bad actors will not follow them. This enforcement mechanism may be called the government, or following the logic of this article, a certain amount of socialism must be inherent in the free-economy for it to function freely. In the real world, a certain amount of economic loss must be accepted so that the economy can function as a free-market. The point is that there is a tradeoff between socialization and freedom where the net economic cost/benefit analysis must be performed. In mixed market economies, the cost/benefit is far, far too high in most industries and a great reduction of socialism is required to regain good economic health. This is not the case in every industry, though. For instance, industries which have a negative net economic value to the economy and society should be purely socialized where the government sets a quota of zero. Such examples are pornography and drug use. Greenspamming would also qualify. A Greenspammer is a change agent who produces misinformation designed to undermine the Christianity of a population in a grifting scheme.

Final Author note:

It is my belief that in heaven there is a perfect free-market economy, because our wills will be fixed for the good. Unless I am mistaken, this is called by theologians as the spiritual economy. If an economy is human relations with an exchange and if our wills are fixed for good, then it follows that every exchange in heaven will be good and, therefore, no intervention is required. In a way, it may seem odd that the strict adherence to the moral law will grant us the most freedom, but as our Lord said: “You shall know the truth and the truth shall set you free”.

- 1. https://crisismagazine.com/opinion/rediscovering-heinrich-pesch-and-solidarism

- 2. https://media.christendom.edu/1996/06/john-paul-ii-heinrich-pesch-and-the-christian-virtue-of-solidarity/

- 3. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23753234.2023.2252488#d1e133

- 4. https://solidarityeconomyprinciples.org/what-do-we-mean-by-solidarity-economy/

- 5. https://www.officialdata.org/us/inflation/1900?endYear=2000&amount=1

This is just a fantastic piece, Ryan. Ties up so many loose ends not explained by the mainstream free market guys.

Thank you very much for the high praise Tim, it was my pleasure. I had been meaning to write this one for a while, so tired of capitalism getting blamed for everything wrong with the economy.

Keep ‘em coming, bro! Have you hard of the landmark court ruling from Western Canada?

I’ll do my best. No I haven’t, what’s going on with you guys?

Basically, the judge ruled that Indian land rights supersede any other private property or Crown land (government) rights. Seems the door is now open for mass collectivization of land.

I looked it up today. But wow! So the tepee-pajeets can just take your land on a whim? Aren’t they just going to claim land rights over all of Canada? What do property rights mean anymore? Who is the judge?

Marxist Israel, like Socialist Venezuela, begins rationing milk amid shortage

https://www.timesofisrael.com/liveblog_entry/supermarkets-reportedly-beginning-to-ration-milk-amid-shortage/